|

|

No, chiggers are not insects, but close enough for this forum... Chiggers (also known as harvest mites or berry bugs) are the juvenile form of mites-- belonging to the class Arachnida, the order Trombidiformes and the family Trombiculidae. Only the six-legged larval stage is parasitic, attaching to various animals including humans by inserting specialized mouthparts into the skin. Contrary to popular belief, they don't burrow under the skin but rather inject digestive enzymes that break down skin cells, creating a feeding tube called a stylostome from which they consume liquefied tissue. This feeding process triggers intense itching and dermatitis that can persist for days after the chigger has detached.

- Chiggers can remain attached to their host for 3-4 days before dropping off, but the resulting itch can last for weeks due to the host's reaction to the stylostome left behind.

- Only the larval stage of chiggers feeds on vertebrate hosts; adult chiggers are harmless predators that feed on small arthropods and their eggs in soil.

- Chiggers are capable of transmitting scrub typhus (Orientia tsutsugamushi), a potentially fatal disease, in parts of Asia, Australia, and the western Pacific.

- In the southern United States, folk remedies for chigger bites have included applying nail polish to "suffocate" the mites—a practice based on the incorrect belief that chiggers burrow into the skin.

- In parts of the UK and Ireland, chiggers are sometimes called "harvest mites" because they're commonly encountered during autumn harvest seasons, leading to traditional warnings about not sitting directly on grass during late summer.

- The term "chigger" is believed to derive from the Chigoe flea (Tunga penetrans), an unrelated parasitic insect found in tropical regions that does actually burrow under the skin, usually in hard calloused skin such as that around the big toe. (I've had my own encounter with the chigoe, in Paraguay. After several weeks of travel there I stopped on a hike because a wart on the bottom of my foot was bothering me... I had been in the habit of scraping it down with a sharp knife whenever it grew large enough to be bothersome. I took off my footwear and began scraping at the wart-- and a clutch of tiny white insect eggs began to spew out. Having known about chigoes, I wasn't too concerned-- but cleaned out the wound and didn't think too much about it... until years later when I realized that the wart, which I had previously treated unsuccessfully with cryotherapy and acid-based pharmaceuticals, had never come back after the ministrations of the flea ;-)

|

| In somewhat related ectoparasitic dynamics, pest control professionals should always ensure that reported “pests” are real and not attributable to “paper mites” or delusory parasitosis issues-- in which clients misidentify-- or imagine-- pests being responsible for symptoms that are, while unquestioningly real, are actually attributable to causes other than pests. |

| |

|

|

|

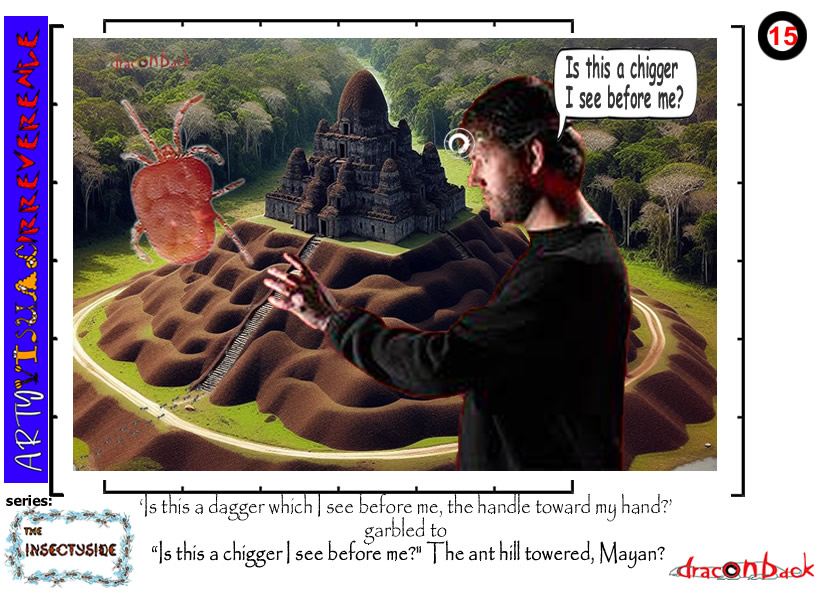

| Although AI did a pretty good job of creating, in the image at the top of this page, an anthill resembling a Mayan temple its unlikely that anthills provided any inspiration on Mayan pyramid architecture. While there are some superficial similarities in form (stepped, tapered structures rising to a point), between the Mayan pyramids, such as the one (shown above left) in Xunantunich, Belize and anthills such as that (above right) in Belmopan, Belize, these likely represent convergent forms owing to the similarities of building techniques/materials rather than any kind of modeling. Wait...XunANTunich...anthill... coincidence?! Nah, hardly even... |

| |

|

|

|

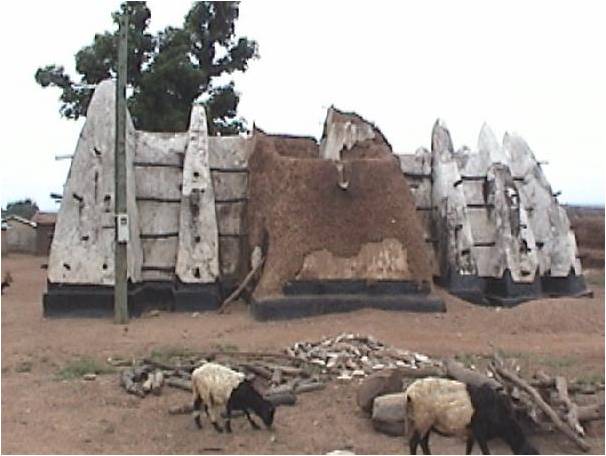

| In contrast, I would argue that the buttressed form of the ubiquitous termite mounds of the Ghanaian savannah (above) probably influenced the traditional architecture exemplified in the ancient mosque of Larabanga (below left)—which in turn influenced the monumental mausoleum (below right) built in the capital city of Accra for Ghana’s first Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah. |

|

|

| |

|

|

Mound-building termites in Ghana (above left) farm fungus, in a way similar to, but distinct from, the way fungus-farming ants do (above right).

The primary fungus-farming termites in Ghana belong to the Macrotermitinae subfamily, particularly species of Macrotermes (like Macrotermes bellicosus) and Odontotermes. These termites cultivate Termitomyces fungi on "combs" made from partially digested plant material passed through their digestive system, their frass, creating a mutualistic relationship where the fungi break down complex plant materials the termites cannot digest themselves, which they then consume for nutrition.

Leaf-cutting ants in Belize are primarily from the genera Atta and Acromyrmex (both in the tribe Attini). These ants harvest fresh plant material which they prepare and incorporate into underground gardens where they cultivate specific Leucoagaricus fungi, actively tending these gardens by controlling conditions and removing contaminants, and then feeding on the fungal tissues as their primary food source. |

|